It’s surprising how some of the problems that haunted India's foreign trade community over two centuries back continue to still. Some day these problems will matter. Today is that day.

Steven Philip Warner | June 2016 Issue | The Dollar Business

History is taught for a reason. You continue to believe it but drawing lessons from the graves to dictate your cerebral existence on an hourly basis hardly sounds an exceptional idea. I mean, how would it have mattered to your choice of something as casual as “What to prepare for dinner?” or as far-reaching as “Where to export?” at this present moment, if your school teacher had floated the idea of John Hanson and not George Washington being the first President of the United States of America? [Hanson was the first President of the US Continental Congress after the Articles of Confederation was ratified in 1781 – eight years before Washington became famous as the Father of the American nation.] The textbook description of innovation and globalisation debunks all theories centered around the past being a near-perfect reflection of the present. America during the Alan Greenspan era, China during the two decades leading to 2014, modes of communication and dissemination of information, coffers of oil-rich countries, seemingly ever-spiralling commodity prices, tax-deferred and debt-funded growth of businesses across Europe, expectations from BRICs, gun-slinging Wild West – this list of ‘how far removed the past is from the present’ is endless. Alright. Telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell is dead. Nokia went from feature phones to feature phones and smartphones, then only to feature phones, and after Microsoft decided to dump even Nokia's feature phones business, Nokia is planing to come back into smartphones! And IBM that was once popular for exporting computer hardware is now earning forex by exporting communication and IT-related services! It's all change out there. That's the only constant.

But not everything respects the rule of time.

The clock does make the present in some instances, an unadulterated reflection of the past. Coincidentally, I felt this pinch for once last month on the day when hopefuls in India’s export-manufacturing community felt “insecure” for the 17th time in as many months. [Insecure? That may sound a clamorous expression for an occurrence that has now become as common as NASA’s complaints about the mercury hitting newer highs. Actually not. Juxtapose India’s performance in the past seventeen months against the same duration leading to March 2005 (when monthly exports from the country crossed the $10 billion mark for the first time), you'll notice that the linear representations of the two event windows make a perfect X. Now that visual comparison can breed insecurity.]

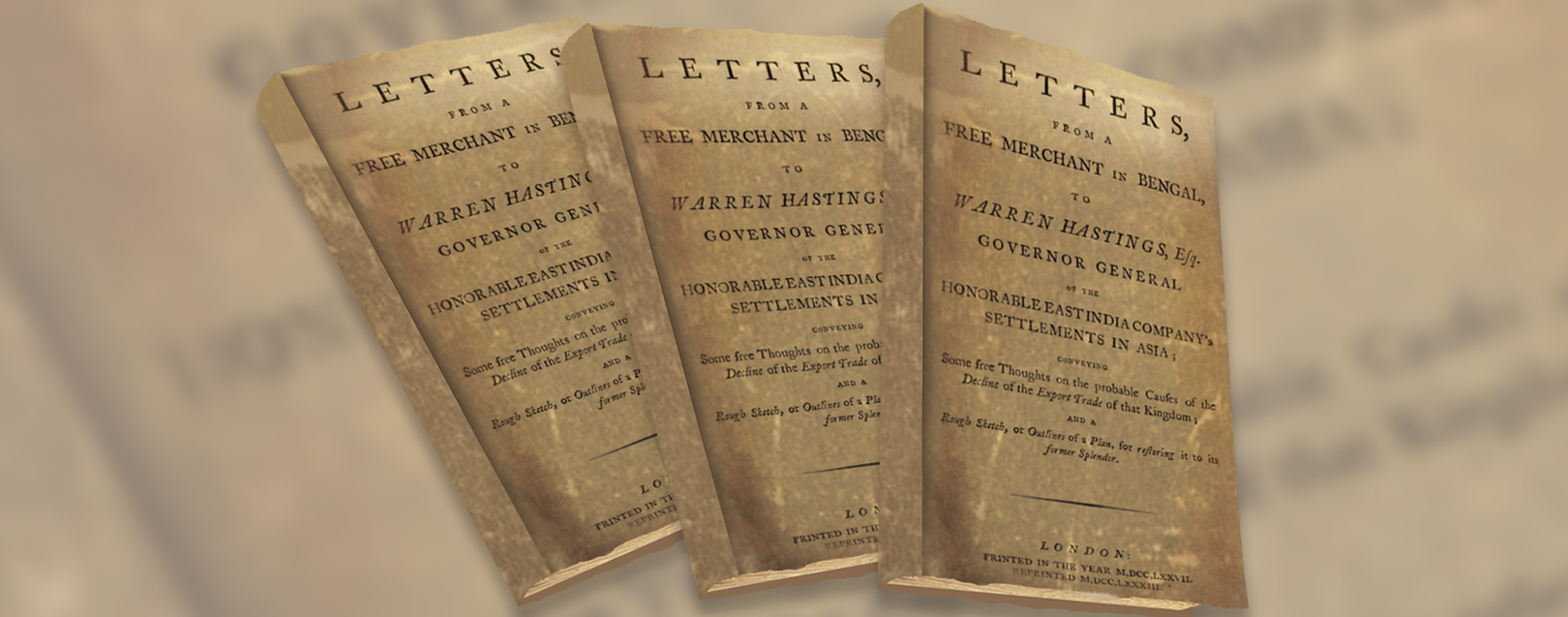

An old friend – popular in his social circles as a voracious reader – came across a wonderful book. He shared the wonderful manuscript with me saying, “History is taught for a reason. But I couldn't read this one.” The book, published in 1783, was titled, ‘Five letters from a free merchant in Bengal to Warren Hastings’. As soon as I started reading the very first line of the opening chapter, I understood why the book was given to me in the first place. Reading it felt akin to stealing honeycomb. Painful. Not because it carries labyrinthine research that makes a commoner feel lost in the alleys of an uninhabited hinterland, but for the fact that it is written in ‘Eignlsh', not English. But for the interesting dramatised account of problems related to India's exports and imports during the British Raj, I would have returned the book instantly. I didn't and read it from head to toe. In the book, the writer, a Bengali merchant argues about the causes of decline in India’s exports in the 1770s. He talks about imports and manufacturing at length too. What’s wonderful is that almost every problem that he discusses seems to have a replica in today’s scenario of India’s foreign trade. He complains of India’s exports declining, Chinese imports hurting Indian producers, inferior quality of goods produced in India, over-invoicing by exporters, increasing trade deficit, levying of excess import duties on raw materials used to produce export items, etc. To quote his letter in unedited form, “The remedy is certain, and within our reach. There is one, and but one remedy for our present. It is the restoring, as soon as possible, of manufactured goods for [foreign] trade to their primitive goodness and price. Our export trade is already extremely decayed... Loading your own articles for exports with heavy duties is contrary to the policy observed by all the States in Europe.” The book is like an Instagram upload of a photo that captures the sufferings of India’s manufacturers and merchants due to unnecessary taxation and lack of incentives for export-manufacturing. So much for the book.

Charity begins at home. And who better than Chinese leaders with the forever etched on their faces Mona Lisa smiles can teach this? I am inclined here to quote a paper titled, 'China’s trading success: the role of pure exporter subsidies’, by Profs. Defever and Riaño of the University of Nottingham – “Behind the meteoric rise of Chinese exports in recent years lies an under-appreciated factor: there is a wide range of government incentives aimed at encouraging firms to produce almost exclusively for the foreign market. These incentives – which we call ‘pure exporter subsidies’ – usually take the form of tax rebates that are conditional on a firm exporting all or most of its production.” In China, companies with a majority of foreign stakeholding that export in excess of 70% of their produce are taxed at levels almost half of the standard corporate tax rates. No tax is charged on profits earned in forex, i.e. all exports! Add to this the SEZ tax benefit, VAT rebates, lower tariff on capital goods imported for export-manufacturing, additional tax benefits on profits reinvested, lower duties on raw materials, direct cash subsidies, discounted utility and land rentals, and easier access to loans; no surprise that over a third of manufacturers in China currently sell over 90% of their products overseas. And here’s the interesting part, ‘accounted-for’ Chinese support to exports currently amounts to close to $200 billion annually – almost 75% of India’s total merchandise exports. The biggest lesson? While Chinese leaders have haggled with lobbies across UN, WTO, etc., who objected to their style of ‘planned governance’, they have always intelligently encouraged exports while keeping their domestic market largely shielded.

Should India ape China's export strategy? Yes. In part. And now.

First and most compelling is the fact that in the second week of May 2016, China’s Ministry of Commerce in its 'Report on Chinese Foreign Trade (Spring 2016)' issued guidelines for greater government support to foreign trade in the weeks to follow, claiming that “the supports from the government to foreign trade development are strengthening.” China’s cabinet has outlined that “a combination of financial, fiscal and land policies will be used”. So at a time when our neighbour has decided to focus increasingly on credit, land and other business promotion policies like encouraging international marketing channels for its exporters and cross-border e-commerce, why should India not execute a similar plan of “conquer the world”? Some do say that this is China’s second shot at stepping on the gas after a rather modest 2015, and government support may not help. Morgan Stanley Huaxin Securities’ chief economist Zhang Jun thinks otherwise. “The governments support for export enterprises in finance and fiscal taxation can help the transformation and upgrading of export industries over a mid to long period of time.” Agreed, developing countries in both Central and Eastern Europe, and those of the former Soviet Union have moved far closer to the free market model – they have evolved by largely trashing the planning model, which has remained an integral part of China’s development strategy over the years. In India’s case however, the same can’t be said. That’s how identical India is to China. There are more striking similarities: population, reliance on import substitution policies, existence of highly capital intensive means of production, etc. Besides incentives, duty exemptions help Chinese exporters. I’d best sum it up in two lines written by Prof. Arvind Panagariya from the University of Maryland, in his academic paper, “China has instituted an elaborate system of duty exemptions on imported inputs used in exports. Total exports associated with concessional import arrangements account for 64% of China's manufactured exports. The country for which the Chinese experience is most relevant is India.”

Premature it may seem, but Indian policymakers have to make amendments at the earliest to get the big outbound ships honking their horns. Remember, foreign trade is a zero-sum game. And instead of waiting each time to call China’s bluff, Russia’s bluff, Iran’s bluff, whoever's bluff, India should move ahead with a determined head on the negotiations table.

Think about India's FTAs. It’s no secret that under the trade pacts that India has signed with developed countries such as South Korea, Japan and ASEAN, it has ended up giving away more market access. Without stringent and internationally accepted rules governing IPR protection, there was little to gain from these FTAs given the already low import duties prevalent on most product lines in these countries. [Read more on India’s experience and future with FTAs in the cover story of this issue.] Not to say that FTAs can be ignored, for their geopolitical reasons are compelling enough – but it would be wiser to focus on FDI and manufacture quality products, help build international channel networks and brands for Indian exporters (exactly what the Chinese State Council decided to do on April 20, in its third meeting of 2016), and focus greater on facilitating e-commerce exports (in this regard, DGFT’s notification no. 2/2015-2020 issued on April 11, 2016, defining e-commerce very "healthily”, thereby categorising sale by Indian e-commerce sellers to consumers overseas as exports and making export benefits their right, is commendable).

It’s surprising how some of the problems that haunted India's foreign trade community over two centuries back continue to still. Some day these problems will matter. Today is that day.

How do First World companies manufacturing orphan drugs command high prices for their patented formulae? These companies – who could easily write off FTAs as just spiritual truths – ensure exports of patented high-quality products that make industry and political groups in the very importing nation (India being one) debate and quarrel over why duties on such products should be 'nil'! Do they therefore even require their countries to sign FTAs?

What India is currently doing is more to follow rules set by WTO’s moral police. There's nothing wrong with that. But to make life easier for India’s exporters during a time when external demands are still weak in general, should be priority. Even if that means rowing

against the tide of textbook obedience.

Are we doing enough? We can analyse this question in the context of three recent developments.

On May 4, 2016, DGFT issued a public notice (No. 06/2015-2020) that introduced changes in Appendix 3B under MEIS. Through this notice, it excused 2787 product lines (eight-digit HS Code) from the need to submit proof of landing, therefore getting rid of the need for Landing Certificate for all 5012 product lines for all markets. Alongside, the fact that the government increased MEIS rates for countries falling under Group C of MEIS from 0 to typically 2-3% was another welcome change. Welcome, but not enough. The markets to which MEIS rates were increased have accounted for 8.8% of India’s total exports in FY2016 so far. Were the rates increased to encourage exports to markets like Tokelau, Antarctica, St. Pierre, Niue Islands, Guam, Nauru, Cocos Islands, Heard Macdonald, Aruba, Eritrea, Faroe Islands, Pitcairn Islands, Saharwi, Palau and Wallis & Futuna Islands? [We will consider ourselves lucky if you knew half of these countries even exist!] Even if we believe that the logic behind increasing MEIS rates to Group C markets was to try and up the shipments to non-traditional and lesser explored markets, then what could possibly be the objective behind ensuring that in over 5,000 product lines eligible under MEIS, the support to the Indian exporter is the same for a market like US, EU, Nepal, Pakistan, Channel Islands, Kiribati and New Caledonia? And why therefore would an exporter choose to export to an island market with just 1 lakh inhabitants like Kiribati (which will be underwater by 2045 as per UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) over a market of 32.5 crore consumers like USA? And if the move to equalise rates has logic, then does it not defy the very reason why rates were increased for the Group C markets or why the three Groups even exist? Baffling! As far as the question of enough is concerned, should India not encourage exports in an environment where the world is overburdened with concerns of falling trade (in CY2015, total world merchandise trade was the lowest in five years) by offering greater relief and cushion to exporters instead of just juggling around with country groups?

Second is the recent talk of a combination of DGFT and CBEC to perform functions as one department under the MoC. This process will only lead to centralisation of authority, greater opacity, and is bound to impact negatively India’s scores in matters like Ease of Doing Business. On one hand, where the country is trying to simply matters for foreign trade and investors, where is the logic in combining two independently functioning department of the government that are currently accountable separately? You must be familiar with the game of cricket. Aren't tasks to bowlers and batsmen unique (in that sense the job of a bowler is to bowl the other team out, so 'negative' purpose that works for his camp; that of a batsman is to pile runs, so 'positive')? But they work together to win as a team. No use imagining you can become a world champion with all all-rounders in the team. That has never happened and possibly never will. DGFT and CBEC are both important arms of the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. They are unique by purpose and design. And their performance can only be judged and improvements introduced if they are allowed to function with separate objectives but for the overall health of the nation’s foreign trade. There is much change yet to be introduced in the manner in which goods are handled and CBEC still has its hands full of trying to achieve something that it already should have by now, like single-window and 24x7 clearance facilities that are aimed at reducing delays in clearance of goods at the ports, quicker examination of export goods by Central Excise officers among others, that increase dwell time and inflate costs for importers and exporters alike. As per estimates by the Commerce Ministry, poor trade facilitation results in cost escalation of Rs.42,000 crore-a-year for the exim community. It’s time we focus on reducing those roadblocks than plan a merger that hardly works even in capitalism.

Third, Make in India. I don’t want to mention job creation or quality here. Just the fact that investment proposals have continued to head south in recent quarters is a concern. In CY2014, proposals in India fell by over 23% y-o-y to Rs.4 lakh crore, which slid by another 23% to Rs.3.1 lakh crore in CY2015. And in the first quarter of 2016, the value stood at just Rs.60,130 crore – if the trend continues, it will be a fall of another 23% in 2016! Clearly, the government has to incentivise foreign and Indian investors, give them greater incentives to set up export-manufacturing bases in India, just like China does!

At a time where deflationary pressures have prevailed in the Indian domestic circuit, you can’t assume that India will forever retain the edge of being a consumer of its own produce! If domestic consumption grows weaker, retail (CPI-based) inflation starts finding it tough to break past the 5% barrier repeatedly as it has happened many-a-time in the past two years, IIP continues to move like a sloth (in April 2016, change in manufacturing IIP was -1.20% y-o-y), oil prices rise because of the ongoing disruptions in Canada and Nigeria causing India’s manufacturing costs and imports to rise (the recent supply shortage around the globe amounts to 3.75 million barrels per day, which is 150% more than the existing supply glut as per IEA estimates), Trump becomes the US President (you know to what extent he could go to distance India and China to reduce US’ trade deficit), the Chinese firewall stays (starving Indian e-commerce companies of the only other consumer market with over a billion souls), and markets like EU, Canada, Argentina and Brazil don’t make exciting macroeconomic progress, India’s export-manufacturing community could be in for bigger shocks.

It’s time we paid heed to a letter that was written 233 years ago by an Indian free merchant to the head of his then-government. Many problems mentioned therein apparently remain the same today. Some day, they will matter.

Today is that day.

Get the latest resources, news and more...

By clicking "sign up" you agree to receive emails from The Dollar Business and accept our web terms of use and privacy and cookie policy.

Copyright @2026 The Dollar Business. All rights reserved.

Your Cookie Controls: This site uses cookies to improve user experience, and may offer tailored advertising and enable social media sharing. Wherever needed by applicable law, we will obtain your consent before we place any cookies on your device that are not strictly necessary for the functioning of our website. By clicking "Accept All Cookies", you agree to our use of cookies and acknowledge that you have read this website's updated Terms & Conditions, Disclaimer, Privacy and other policies, and agree to all of them.